Rental housing’s long-term investment outlook remains head and shoulders above its peers, driven by structural supply constraints and steady demand growth, finds the 2026 Emerging Trends in Real Estate report. Explore this trend and other key takeaways from the 47th edition of Urban Land Institute (ULI) and PwC’s influential industry report.

Key Findings

- The pandemic has created a two-tier economy where higher-income people who are able to work from home have regained employment, while those in high-touch industries remain unemployed

- Shelter-in-place measures coupled with the closure of offices, gyms, restaurants and other leisure outlets have driven a huge demand for more space in less dense, suburban areas

- The first half of 2021 will resemble much of 2020, but widespread vaccinations should begin to ease the abnormal market dynamics by September

Overview

Recessions tend to be viewed through the lens of the previous crisis. This was certainly true in the early months of 2020 when COVID-19 brought the U.S. economy to a halt and credit markets froze. Those of us who lived through the Great Recession feared the makings of another financial crisis and braced for a blow to real estate markets. What has occurred since, however, has defied many of those fears. A financial crisis never materialized, people have continued to pay their bills, and almost paradoxically, the housing market has boomed. While counterintuitive, these dynamics have been driven by the unique nature of the crisis.

What happens in the economy over the next six to eight months and years ahead will largely depend on the success of the vaccine rollout, the strength of fiscal policy, and how deeply the COVID-induced behavioral shifts have become ingrained in households and businesses.

Sign up to receive Arbor's content in your inbox.

Share:

A Recession Unlike Any Other

Understanding the atypical nature of the crisis provides insight into the path of the recovery. The current downturn has been fueled by an external health event – a pandemic – not fundamental weakness in the economy. Most of the impact has come from changes in behavior: changes designed to avoid the spread of the virus, and changes to adapt to living with the virus. This is very different from recent recessions where bubbles burst and sent the economy into a tailspin, such as what happened when tech stocks collapsed in 2000 and the housing market fell apart in 2007.

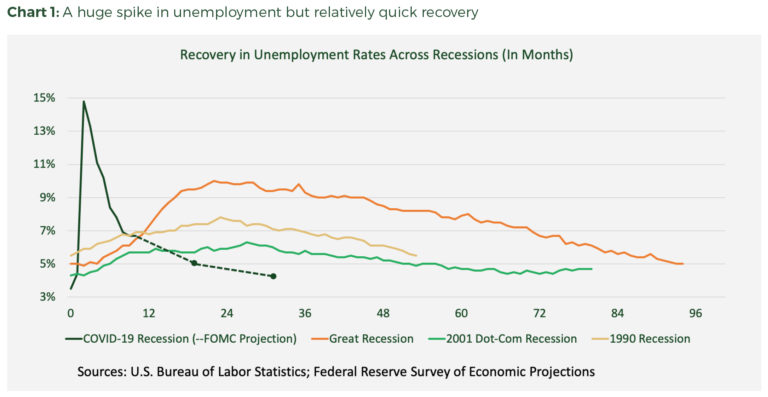

The earliest and most significant blow to the economy came from measures to alleviate the spread of the virus. As people sought to protect their health and governments enacted statewide lockdowns, the economy came to a standstill. In the first months of the crisis, 22 million Americans lost their jobs, and the unemployment rate shot up from 3.5% to nearly 15%. However, unlike prior recessions, the vast majority of these early layoffs were temporary and quickly reversed as the lockdowns eased. This is why the unemployment recovery has been quicker than expected and is set to outpace that of previous recessions (Chart 1).

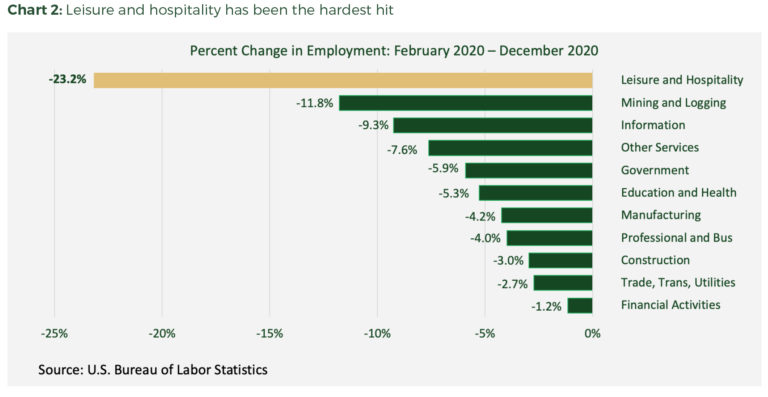

Even as parts of the economy have bounced back, health concerns and new lockdowns have driven an uneven recovery. Employment losses remain significantly elevated in high-touch service industries, such as leisure and hospitality, that struggle to limit in-person interaction and often face mandated restrictions (Chart 2). On the other hand, employment in sectors such as financial services has nearly recovered. This has created a two-tier economy where those who can work from home, and typically earn higher wages, have regained employment, while those who are in high-touch industries remain unemployed.

The avoidance of specific types of businesses have flipped recessionary dynamics on their head. Typically, it is the goods-based sector of the economy that suffers during a downturn. But because consumers are constrained in their ability to spend on experiences, their only outlet is to spend on things. The two-tiered recovery explains half of the uncharacteristic housing boom. As higher-wage workers have regained their jobs, they have been able to benefit from ultra-low interest rates and generous work-from-home policies. The other half can be explained by the importance housing has taken in peoples’ lives as they adapt to living with the virus. Shelter-in-place measures coupled with the closure of offices, gyms, restaurants and other leisure outlets have driven a huge demand for more space in less dense, suburban areas. Similarly, because people are relying on their homes to provide for more aspects of their lives, they have prioritized paying their rent and mortgages. This is one of the reasons why housing across most asset classes has held up well.

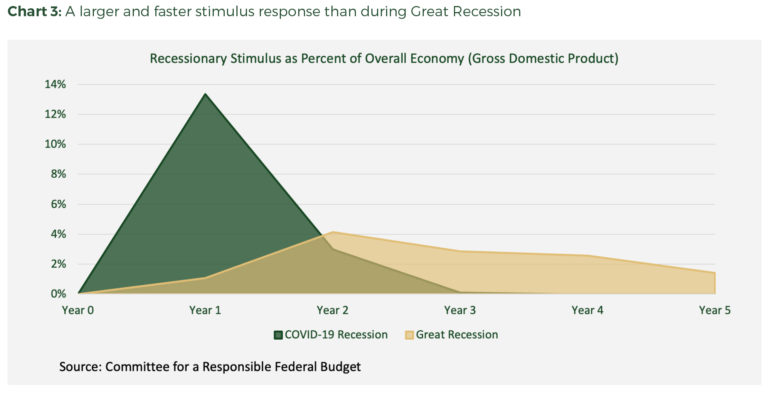

Perhaps the most significant differentiator of the COVID-19 crisis has been the response from policymakers. In March 2020, Congress passed the largest stimulus plan in U.S. history – the $2.2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. The CARES Act not only dramatically expanded the scope of those eligible to receive unemployment, but it boosted those benefits by $600 a week and issued individuals $1,200 stimulus checks.

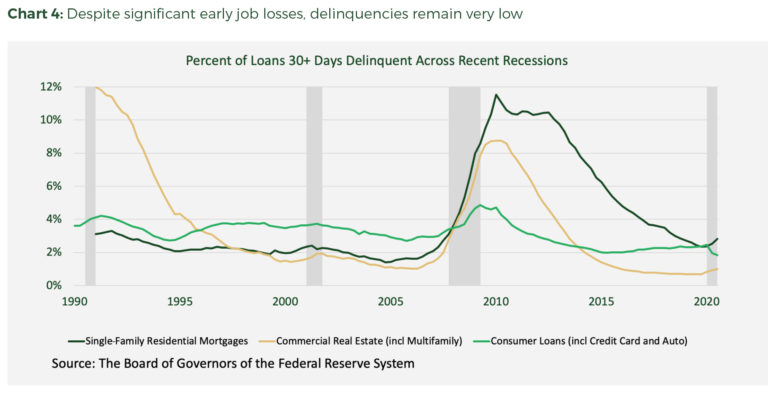

Together with five other bills, including the $900 billion year-end follow up to the CARES Act, the support enacted by Congress in 2020 far surpassed the stimulus response during the Great Recession (Chart 3). Combined with mortgage forbearance measures and moratoriums on student loan debt payments, the aid provided by Congress has been able to keep households afloat and delinquencies low (Chart 4).

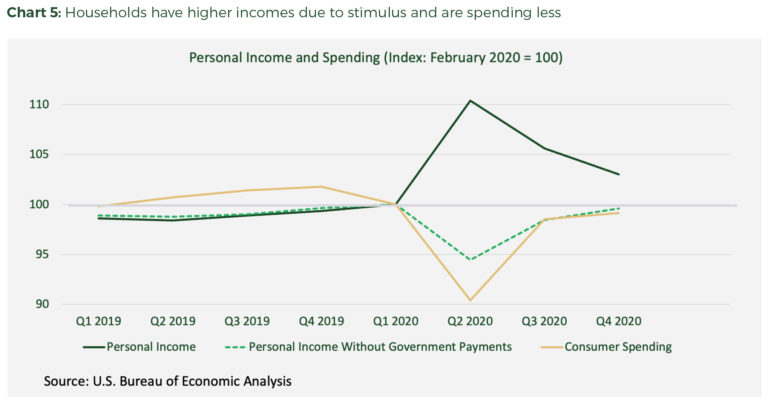

A New Year, a Similar Economy

The first half of 2021 will resemble much of 2020, but widespread vaccinations should begin to ease the abnormal market dynamics by September. The trends that persisted for much of last year will continue in the first few months of 2021. As COVID-19 continues to stress healthcare systems around the country, high-touch businesses will be plagued with stop-and-go reopenings. This will maintain pressure on individuals who rely on those industries for employment and keep layoffs elevated. However, similar to what we saw with the CARES Act, the stimulus that passed at the end of 2020 should support incomes and households through the winter months (Chart 5). With elevated incomes and fewer outlets for spending, delinquency rates should remain low as people continue to focus on important bills such as their rent and mortgage payments.

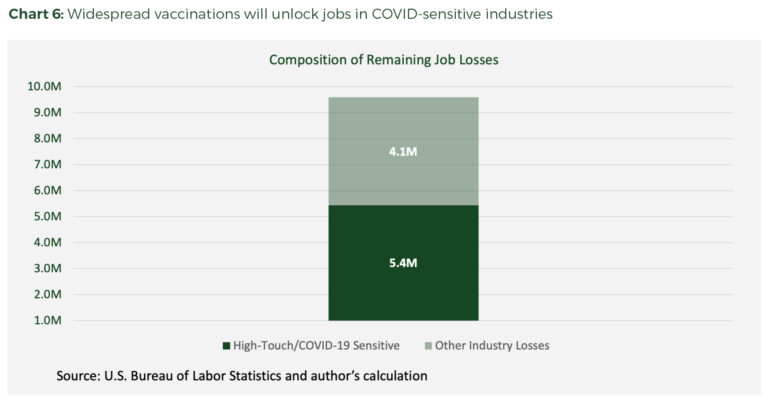

While the labor market will continue to improve throughout the year, the progress will not be linear. Nearly 60% of remaining job losses are in high-touch industries (Chart 6). Employment at hotels, restaurants airlines, daycares and other COVID-sensitive businesses will be essentially locked-up until the health concerns are addressed. Until then, job creation will be slow and limited to industries that are able to operate under work-from-home models. Education and health services could also see a boost as the Biden administration has prioritized the reopening of schools, and hospitals seek to address significant worker shortages. As states begin to achieve widespread vaccinations, the initial rebound in the hard-hit industries will likely be rapid, but regional. States that are more efficient with their vaccination programs and those that have lower population density will see the benefits first.

One of the biggest challenges for Congress in 2021 will be to avoid stimulus fatigue. While there is another relief package already being discussed, many people who work in high-touch industries will need ongoing and targeted support throughout much of the year.

The perfect, positive storm for suburban housing will continue in 2021 and will further drive interest in single-family rentals. The housing market drivers of 2020 are not going anywhere. Mortgage rates should remain near historic lows as the economy recovers and the Federal Reserve continues to purchase longer-term treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. The push for more space will keep people looking for single-family homes with home offices and gyms. While the lack of inventory and rising prices may begin to dampen the purchase market, it should drive further interest in single-family rentals. Potential first-time homebuyers who may be facing affordability issues or those looking to try out suburban life before purchasing will likely turn to rentals. Additional fuel could arrive in the form of student loan forgiveness that could further boost demand from millennial homebuyers.

Beyond 2021

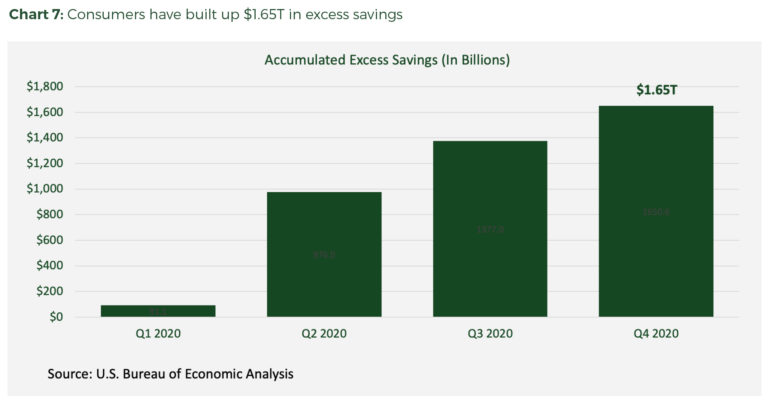

As the economy returns to more normal conditions in the fall of 2021, we will get greater insight as to what the future holds. One of the most significant factors in the strength of the post-vaccine rebound will depend on the amount of excess savings consumers are holding. Throughout 2020, the strong stimulus from Congress and limited outlets for spending have allowed consumers to sock away $1.65 trillion in excess savings (Chart 7). If these savings are unleashed in a meaningful way in hard-hit service industries, then we could see a significant economic rebound in late 2021 and 2022. However, if consumers have become more wary of future economic weakness or if the preference for savings has shifted higher, then the bounce could be weaker than expected.

Some of the behavioral shifts that have developed during the pandemic will persist. The move away from densely populated spaces is likely to be one of the most ingrained changes. Not only are people moving out of the urban cores and into suburban areas, but those transitions are likely to be enduring. Once people start becoming part of their new communities, sending their kids to school, and filling their larger spaces with home offices and gyms, it makes the transition back to smaller, urban markets more difficult. This dynamic should continue to drive the single-family purchase and rental markets, along with suburban multifamily units.

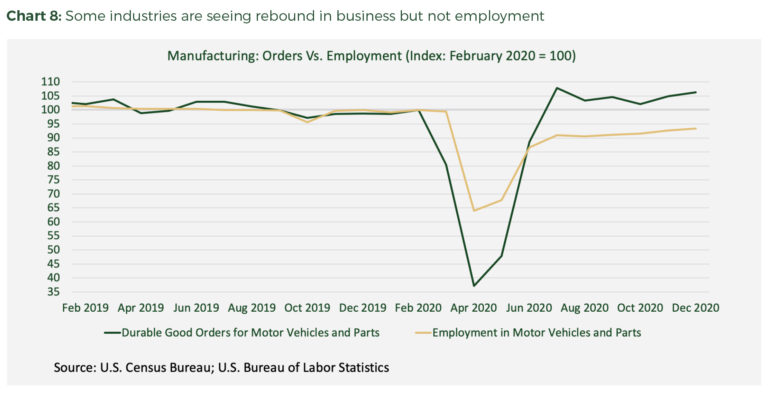

When looking at the employment picture, it is possible that many of jobs lost early in the crisis will be recouped by the end of 2022. However, investments made by some industries and businesses to get by with fewer workers and less dense workspaces may change the landscape. Industries such as manufacturing have seen a significant rise in business but not in employment (Chart 8). While this could be a temporary phenomenon, the longer this trend persists, the more likely it could become permanent as companies make technological updates. This is something to watch as more businesses will be required to alter how they operate in order to maintain safe working conditions.

The COVID-induced recession has been unlike any other downturn we have experienced in modern history. The acute shock to the economy has not been driven by fundamental weakness, but by measures to avoid and adapt to living with the virus. How the recovery proceeds over the next six to eights months will largely depend on the success of the vaccination rollout and the strength of fiscal policy. The people and industries that have been most impacted cannot be allowed to fall through the cracks, or this abnormal recession risks turning into a normal one. What happens to the recovery over the longer term is more difficult to predict. It will only become apparent when we can answer the question: how deeply has the pandemic permanently altered consumer and business behavior and changed the fabric of our economy?

For more research and insights, visit arbor.com/articles

Disclaimer All content is provided herein “as is” and neither Arbor Realty Trust, Inc. or Chandan Economics, LLC (“the Companies”) nor their affiliated or related entities, nor any person involved in the creation, production and distribution of the content make any warranties, express or implied. The Companies do not make any representations regarding the reliability, usefulness, completeness, accuracy, currency nor represent that use of any information provided herein would not infringe on other third party rights. The Companies shall not be liable for any direct, indirect or consequential damages to the reader or a third party arising from the use of the information contained herein.