What the End of the Eviction Moratorium Means for Multifamily

- SCOTUS issued a ruling on Aug. 26 that blocks the CDC’s eviction moratorium, offering a reprieve to small landlords.

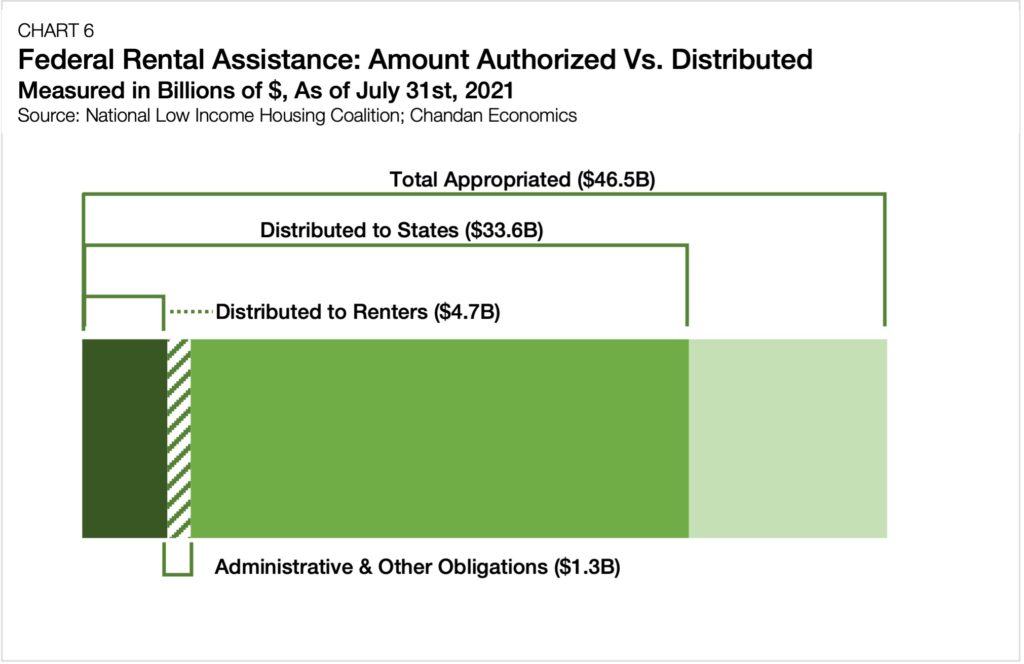

- Of the $47 billion in federal funding appropriated to address rental assistance, only $4.7 billion had been distributed to renters as of July 31.

- Employment growth totals for low-income earners trails middle- and high-income earners, putting added financial pressure on low-income renters.

Key Takeaways

An evolution of the federal eviction moratorium reached a dramatic ending on Aug. 26. The Supreme Court of the U.S. (SCOTUS) ruled that the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lacked the authority to maintain the policy without congressional action.

The decision came as the debate over the CDC’s policy had filled the airwaves in recent weeks. Policymakers, advocates and industry leaders attempted to balance the needs of low-income tenants at risk of eviction with the concerns of small landlords bearing the brunt of the moratorium’s financial burden.

Eviction Moratorium Debate

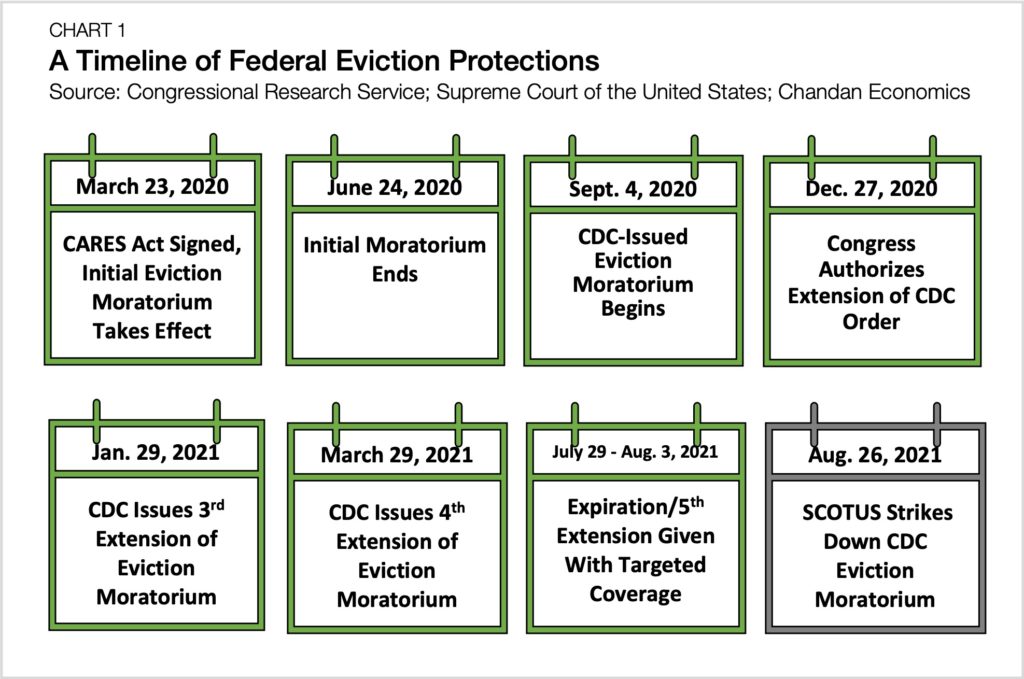

The federal government maintained a nationwide pause on evictions since the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was signed into law on March 27, 2020. With an original expiration of July 2020, the CDC extended the moratorium several times to prevent a wave of homelessness amid an enduring pandemic (Chart 1).

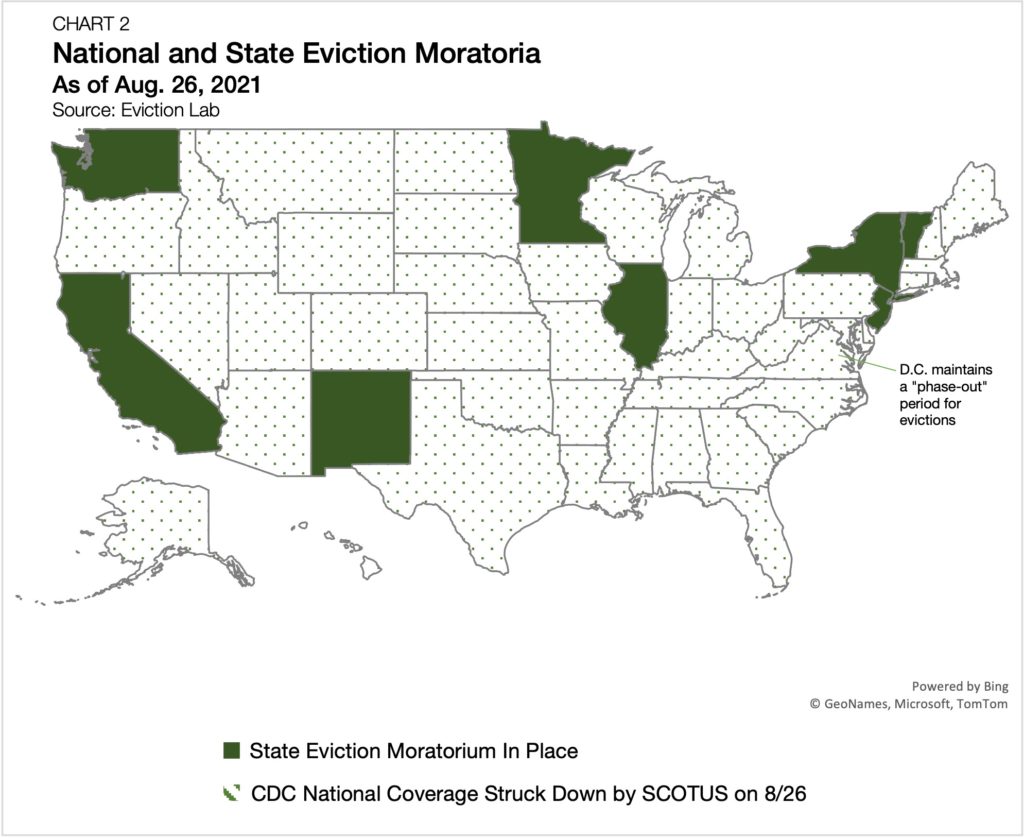

The most recent extension of the eviction moratorium covered roughly 80%[1] of all renters and had an expiration date of Oct. 3. Still, several states have their own moratoria with various summer and fall end dates (Chart 2). In a statement released by National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC), the advocacy group was deeply critical of the moratoria’s continuation, asserting that it was “unacceptable to continue to ask housing providers to carry the financial burden of this pandemic.”

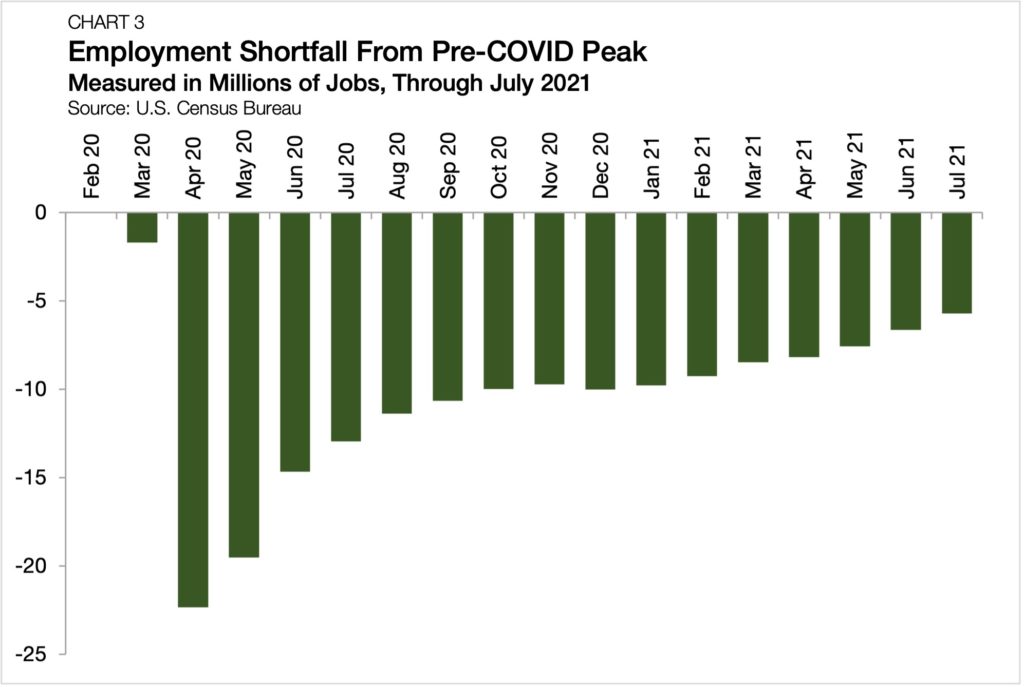

The benefit of a national eviction pause at this stage in the pandemic is a source of debate. On one hand, the economic impact of the pandemic remains sizable. Employment levels in the U.S. are still 5.7 million jobs below their February 2020 peak.[2] Additionally, the Delta variant is keeping the public health crisis in focus.

On the other hand, nearly $47 billion in federal aid has been appropriated to assist renters. According to a Chandan Economics analysis, there is more than $4,000 of appropriated federal rental assistance for every rental household that has missed at least one rent payment in the 12 months ending first-quarter 2021.[3]

However, only $4.7 billion of those funds had been distributed to renters as of July 31. While rental assistance has provided a lifeline for many constrained renters, several states have faced challenges in its rollout. Rigorous application requirements, some of which go above what is required by federal law, have frustrated many applicants. Furthermore, matching funds to those most in need comes with its inherent challenges, such as program awareness and access to application resources.

Potential Eviction Wave

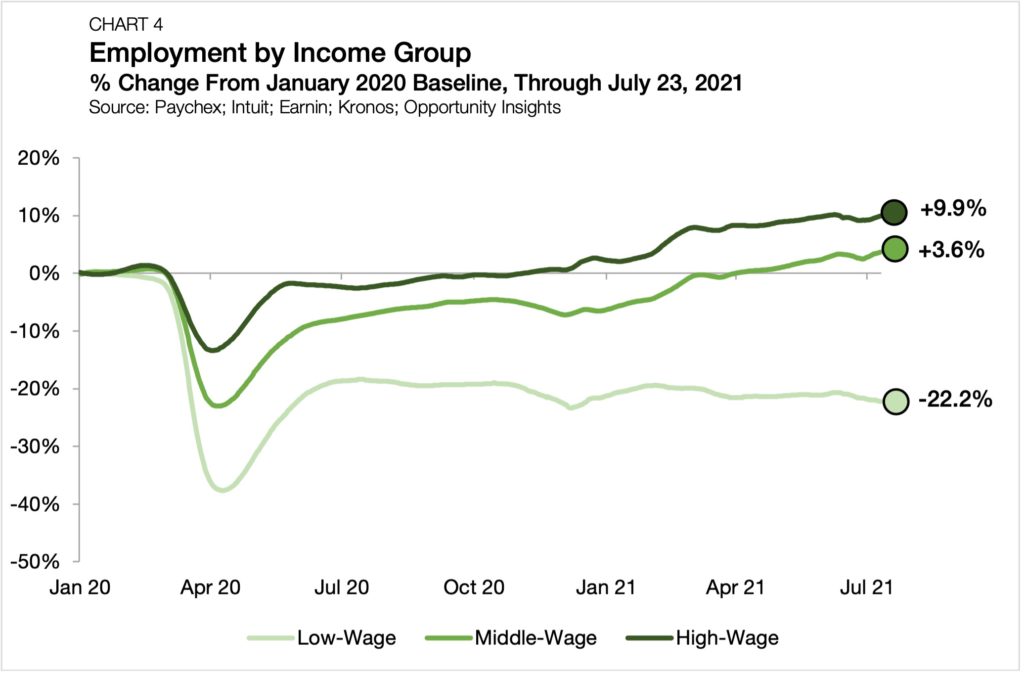

At the heart of the eviction moratorium extension discussion were concerns around the pandemic’s continued economic impact on renters, especially those at the lower end of the income distribution.

According to U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey (HPS) results from the period of Aug. 4 to Aug. 16, 43% of renters felt that they were either “somewhat” or “very” likely to be evicted in the next two months. Broken down by income, lower-income[4] households unsurprisingly remained more pessimistic than higher-income households.

A 47% share of renter households making under $75,000 per year feared they were likely to be evicted within the next two months, compared to just 20% of those earning between $75,000 and $100,000 per year. While the actual eviction risk is likely lower than what estimates based solely on the HPS might suggest, the population of vulnerable renters is significant.

Uneven Labor Market Recovery

A key driver of the eviction fear is the sluggish labor market recovery, which has put added pressure on household finances. Through July, the U.S. economy has recovered 16.6 million of the 22.3 million jobs lost at the outset of the pandemic, an impressive speed of recovery but still 3.7% below pre-COVID levels (Chart 3).

The labor market recovery has also been uneven. Opportunity Insights found that through July 23, 2021, employment among low-wage workers (defined as those making $27,000 per year or less) was down by a dizzying 22.2% from January 2020. Meanwhile, middle-wage workers (earning between $27,000 and $60,000) saw employment rise by 3.6% over the same period. Employment of high-wage workers (earning above $60,000) had risen by an impressive 9.9% (Chart 4).

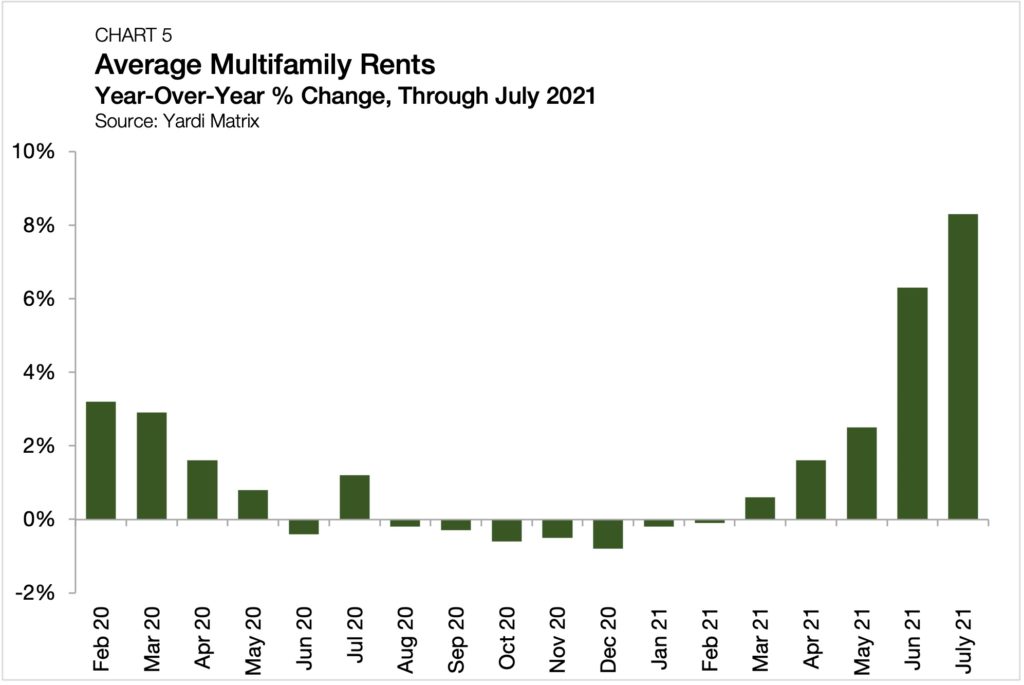

Another challenge for low-income renters is that rents have also begun to rise. According to Yardi Matrix, multifamily rents increased by an extraordinary 8.3% year-over-year in July — the largest 12-month increase in the history of Yardi’s tracking (Chart 5). Following seven straight months of year-over-year declines, multifamily rents have now increased on an annual basis for four consecutive months.

The persistent labor market slack, rising rents and worsening renter sentiment about the ability to make payments will likely contribute to an increase in evictions. Since March 2020, nearly half a million evictions have been filed despite protections against their enactment. Roughly 6,500 were filed in the latest week of data availability (through Aug. 21), according to Eviction Lab.

However, projections for the potential wave of evictions range widely. A recent report by Goldman Sachs estimated that 750,000 households could be at risk of eviction over the next few months if rental aid continues to slow-roll while eviction protections are lifted. Upper estimates project that up to 11 million renters could be at risk of eviction absent the federal protection.

Eviction Moratorium Impact on Small Landlords

While much of the focus has been on addressing tenant needs, the stress on small landlords is a significant issue. Large, professionally managed apartment properties showed resilient collections through the pandemic, while smaller properties and landlords struggled.

According to the NMHC Rent Payment Tracker, which surveys collections from large, professionally managed multifamily properties throughout the nation, 94.9% of apartment households made a full or partial rent payment by the end of July. This year’s levels are just 170 basis points (bps) below July 2019, when the U.S. economy was operating near its pre-pandemic peak.

Meanwhile the collections data is less clear for smaller landlords and those serving primarily the lower-income segments of the population. According to a 2021 study by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University (JCHS) that surveyed rent collections in the Albany and Rochester, New York areas, rent collections by small landlords were down 26.1% in October 2020 compared to the year before.

Small, independent owners supply nearly three-quarters of all U.S. rental homes. Relative to larger landlords, they are more likely to rely on their properties as a primary source of income.

Additionally, the slow distribution of federal rental assistance has meant smaller landlords who are more likely to own properties in low-income communities have had to foot much of the bill (Chart 6).

Next Steps

The national eviction moratorium was an emergency measure that was always meant to be temporary. Even though the pandemic called for such a significant reaction, as the recovery continues to take center stage, market participants and regulators alike are beginning to focus on practical long-term solutions.

Accelerating the delivery of rental assistance to at-need residents is likely the most immediate and direct-action state governments could take to alleviate eviction risk.

On Aug. 25, the White House and Treasury Department announced new efforts to accelerate emergency rental assistance to at-risk renters. Specifically, Treasury will now allow eligible grantees to self-attest their need without additional documentation to increase aid distribution.

The Administration is also seeking the help of nonprofits that can extend lines of credit to at-need families while they wait for their applications to be processed. Additional efforts will likely be evaluated to distribute assistance more efficiently. However, shifting the focus toward aid and away from blanket eviction protections is a potential first step.

For the latest research and analysis on the housing market, visit arbor.com/blog.

Footnotes

[1] Based on communities that were experiencing a surge in COVID-19 cases on Aug. 3, 2021.

[2] Based on Chandan Economics analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data through July 2021.

[3] Estimate is calculated using U.S Census Bureau’s. homeownership rate and household estimate data, as well as Research Institute for Housing America’s study, “Housing-Related Financial Distress During the Pandemic” (Accessible here).

[4] “Lower-income” here is defined as households earning under $75,000 per year, while “higher-income” are those making between $75,000 and $100,000 per year.